Northrop Grumman site director helps close the STEM gap with the SAE Foundation

Rick Kettner says he enjoys seeing “lightbulb moments” happen in the classrooms where he serves as an AWIM program volunteer.

“The Straw Rocket project is always fun with the younger students. It is elegantly simple, yet captures the students’ attention and provides opportunities for imagination.”

Straw Rockets, Gravity Cruiser, Skimmer, Motorized Toy Car, Pinball Designer — these seemingly unusual names are familiar to Kettner and his teams, who have supported a number of SAE’s A World In Motion (AWIM) challenges.

“Each of these projects offers an amazing foundation for learning and creativity,” Kettner says, and he would know. In his role as site director at Northrop Grumman, Kettner brings 30 years of experience to overseeing the engineering process, including design, implementation, testing, and manufacturing in addition to new business and administration.

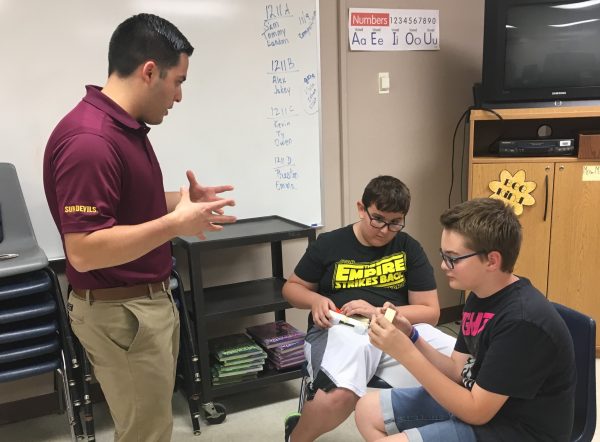

Students with Kettner working on the AWIM JetToy Challenge

For the last seven years, he’s also concentrated on inspiring the next generation of engineers in Gilbert, Arizona, located in the southeast Phoenix metropolitan area. He’s introduced STEM career possibilities to students at almost every age — from second-grade classrooms to high school and beyond with the Chandler-Gilbert Community College’s Hermanas initiative focused on introducing Latinas to engineering careers.

Rick found that AWIM helps fill in the skills that aren’t fostered in a typical education.

“For years we would find tremendous talent technically,” Kettner says. “They had the math, they had the physics, they had the fundamentals, but many of them didn’t have the soft skills: being able to work in teams and being able to think when an odd problem was sent their way.”

SAE’s Pre-K–8 AWIM focuses on developing students to enhance important 21st-century skills such as communication, collaboration and critical thinking.

“The end goal isn’t to just get a degree or get them in school,” he says. “It’s really to map the pathway to their first real job.” Kettner adds that the main reason he volunteers in AWIM classrooms is for the students and teachers.

“The students clearly enjoy the hands-on projects and the practical learning. But just as important are the benefits for the teachers,” he explains. “Many K-12 schools are struggling today with budgets, to challenge and stretch students and to provide variety to an often basic and rudimentary curriculum. In each of our experiences, the teachers have been so appreciative and really look forward to the AWIM days.”

Kettner says that AWIM’s particular model, providing curriculum and volunteers from industry directly into the classroom, helps address the constant challenge of funding.

“We have a number of folks who are more than willing and capable to engage on a volunteer basis, and that’s why it’s been so popular here.”

“We have a number of folks who are more than willing and capable to engage on a volunteer basis, and that’s why it’s been so popular here.”

Kettner recalls volunteering with the Pinball Designers Challenge. Students get hands-on experience with the concepts of gravity, potential and kinetic energy and inclined planes by working in teams to build, test and modify a non-electronic pinball machine.

“It’s fun with the second-grade class … to see creativity and different trials,” Kettner says. “Thinking through a bunch of what ifs and problem solving is a tremendous skill that helps one develop into an engineer, a manager of engineers and director of groups of technical people.”

And it makes an impact in the STEM gap. Administered by teachers and assisted by industry volunteers, AWIM brings science, technology, engineering and math education to life for pre-K–8 students. Kettner is one of more than 30,000 volunteers who’ve reached more than six million students since 1990. The SAE Foundation provides teachers with professional development to confidently guide students through STEM fundamentals, with challenges for a variety of different ages.

“Problem-based projects help give them that context and ability to take it further,” Kettner says. “When they’re first exposed to math and science, it’s hard, it’s not intuitive, then they get frustrated and say it’s not for me, maybe I’ll go do something else. By making it more fun, understandable and practical, we can carry it further.”

Kettner explains that STEM careers are at a critical point as current engineers are retiring.

“This comes at a time when tech is in everything, specifically in the space and aerospace business,” he says. “There’s an unprecedented need going into the defense industry, and all kinds of commercial ventures. All these things that we’re taking on as a country and a society that we need people to fill.”

Career decisions are made around the fourth- or fifth-grade level, he continues.

“Looking at their parents, teachers, (students) may not see an engineer, may not even know what that means. The more we (practicing engineers) can reach out into schools and into the community, the more we can help them understand that it’s not a huge leap, not a huge barrier, to getting into an engineering career.”

The volunteer experience has been personal to Kettner. He says his two daughters both had great experiences in school with experiential learning, and his younger daughter has recently begun her career in mechanical engineering.

“It is really exciting to engage with younger students starting the pathway and knowing where it can lead,” he says. “Specifically, for younger female students, it is very rewarding to see their eyes opened to career fields they might not have known were available.”